Pandemonium

In spring 2001 when I was visiting London, a respected colleague from the Tate Modern recommended that I “see” Janet Cardiff’s piece at the Whitechapel Library. I was curious. What sort of contemporary art would the historic Whitechapel Library display? Because of the high recommendation, I went the very next day.

When I was asked to surrender my ID I was confused. When the librarian handed me an mp3 player and headphones, I was even more surprised.

When I turned on the headphones and turned on the player, I heard a woman’s voice that was so vivid I kept turning around to see who was standing so uncomfortable close to my back. The art that I expected to see, I discovered, was an experience. I was to become part of the story she was telling, moving through the streets of London, part of the drama that was unfolding, an observer of the city’s history. So many levels of storytelling made the realities an exciting challenge. When I completed the walk, I had “traveled” through the century and to foreign lands, my heart pounding with fear from the sounds of warfare and the footsteps that wer following my. I was captivated and wanted to learn more about Janet and her magical work. I wad one overwhelming goal – to being this intriguing artist to Philadelphia, and Eastern State Penitentiary, the abandoned and ghostly 19thc. Prison seemed like an inspirational site for such a project.

Janet Cardiff collaborates with her husband, George Bures Miller. Together they create experiences at a level of observation and sensitivity that we are rarely exposed to. When I had contacted Cardiff and Miller, they had just been awarded the prestigious La Biennale di Venezia Special Award for their piece the Paradise Institute. Now every curator in the world, or so it seemed, was clamoring for their attention, and I had to wait at the end of the line.

But they did give me the go ahead to apply for a PEI grant and, depending on their schedule, would plan a visit to Philadelphia. In December, a most inhospitable time at Eastern State, the cold is bitter and the wind whips around even when you are inside. I was afraid they’d be horrified, but the place worked its magic on the artists, as it does every time I visit. They were especially taken with cell block seven, a gorgeous two story cell block, the last of the originally designed cell blocks by John Haviland.

Their proposal was to turn the cell block into a musical instrument of sorts. Their idea was to create a cacophonous sound piece that would recreate the “pandemonium” of a prison riot. Since Eastern State was known for its silence, and the inmates were not permitted to communicate at all for the first sixty years of its existence.

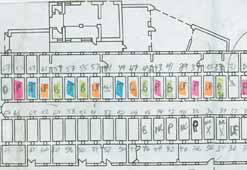

The “instruments” were made of computer-driven beaters, like drum sticks, felted drum heads, metal rods, and were intended to beat on prison furniture – the cupboards, bed frames, metal lamps, toilets – whatever remained in the deteriorated cells. There were tense negotiations with the protective Penitentiary staff. After all, these were historic artifacts. Finally they were granted permission and worked on the piece, day and night for five weeks. Their installation was assisted by Philadelphia artist, Richard Harrod, and Carlo Crovato, who came with George from Germany. Toward the end of the wiring and placement of the equipment, Cardiff arrived with their tonnemeister, Titus Maderlechner, who assisted the artists with the composition as well as the computer technology.

Pandemonium was a haunting piece, still remembered by those who saw it five years ago. It capitalized on the emptiness of the prison, and the sound re-creates the world of the inmates – the isolation and their attempts at communication.

In the catalogue, Richard Torchia remarked, “…both artists frequently cast the spectator in the role of the protagonist who is invited to negotiate that slippery space between seeing and hearing.”

Sean Kelley wrote, ”In its chaos and clatter, Pandemonium evokes the penitentiary’s troubled past. I walked through the piece with a former inmate, who found the piece deeply moving and disquieting.” The inmate remarked, ”The worst part is when it (the piece) is silent.”