Bruce Pollock, Vas Hermeticus

Jonathan Borofsky, Dark Flying Figure for Eastern State Penitentiary

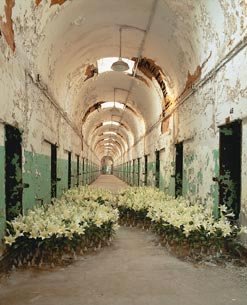

Virgil Marti, For Oscar Wilde

Carolyn Healy and John Phillips, Overtones

Winifred Lutz, Serving Time

Prison Sentences: The Prison as Site/The Prison as Subject

Co-Curated by Julie Courtney and Todd Gilens

When Todd Gilens asked me if I’d like to see Eastern State Penitentiary, the abandoned 19th c. prison in the Fairmount Section of Philadelphia in 1990, I jumped at the chance. Eastern State was one of those amazing wonders of Philadelphia, looming, and forebodingly large. His friend Sally Elk worked for the Historical Commission of Philadelphia and there was much discussion of what should be done with this behemoth on 11 acres of prime real estate in the city.

I was completely unprepared for my reaction when we finally went into the prison. Its forbidding exterior gave no warning of the heart-wrenching ruined, deteriorating interior. I had no idea that the cathedral-like cellblocks and lighting would be so awe-inspiring. I had to keep reminding myself that this incredible beauty was not what the inmates experienced, locked away in solitary confinement, the only light coming from the small sliver of a skylight.

There was no question in my mind that artists should be invited to spend time in there and develop projects that addressed the many issues of the penitentiary – the amazing architecture, the desolation and isolation that caused mental illness, issues of criminology today, and the palpable fear that inmates suffered that still can be felt while wandering the vast cellblocks today.

Thus began a five-year journey of our conceptualizing a project and applying for funding to support such an endeavor. It took us five years to raise the money. Early on we sought advice from friends and funders. Ella King Torrey at the Pew Charitable Trusts was one of our earliest advisors. The National Endowment for the Arts awarded us our first grant, and with their support we were able to raise the rest of the money. We were unbelievably lucky to have met Ken Brecker during his brief tenure at the William Penn Foundation. Ken happened to live near the prison and was so excited and supportive of our project that he awarded us a very large grant. That, too, brought in other funders, such as Andy Warhol Foundation, and Rockefeller, to name a few. It was a fresh idea and the funders were enthusiastic to put their names on it.

We tried to cast a wide net for artists to include people near and far to come and see the site. Ultimately 75 people responded and we selected 14 projects. The artists ranged from the internationally renowned to local and emerging artists. Some artists chose to use an entire cellblock and some used only one cell. As one of the artists Christina Kubisch said, “We are all looking at the same place and making what we see there, but it comes out so differently.” Indeed, the 23 artists did interpret the penitentiary in such different ways.

Beth B: A Holy Experiment

A door slams shut as you enter the cell. The visitor is locked in. A syrupy, threatening voice says “Come a little closer..”. In an adjacent cell viewers watch the trapped victim’s reaction.

Jonathan Borofsky: Dark Flying Figure and Dream Room

One of Borofsky’s signature flying figures looms above the entrance gate; in two cells were drawings of Borofsky’s dreams, very likely similar to the kind of dreams an incarcerated person might have.

James Casebere : The Model Room

The mad fictional architect who designs institutional buildings made for the control and management of others, goes berserk leaving dozens of models to decay, just as Eastern State has.

Malcolm Cochran: Soliloquy

Interested in the fact that women were in the prison, Cochran made a video of a woman braiding her hair while a giant braid tied to the bed frame climbs out the skylight, over the interior road and over the 30’wall. The braiding signifies the busy work often assigned to prisoners.

Willie Cole: 5 to 10

Discarded and broken playground equipment refers to the broken children who played on them. This bittersweet playground reminded us of the complex broader issues of childhood and parenting.

Simon Grennan and Christopher Sperandio: Life in Prison

A graphic novel depicting a prison in Manchester,England that was based on the same plan as Eastern, juxtaposed with images from Eastern with stories of people in the prison with the artists and curators.

Carolyn Healy and John Phillips: Overtones

An installation of objects filling every cell in a cellblock accompanied by a poetic audio installation, referred to the madness of the incarcerated.

Homer Jackson and Mogauwane Mahloele with John Abner, Richard Jordan, and Lloyd Lawrence: Why Malcolm Had to Read

A multi-media installation in an entire cellblock by artists who have spent years teaching in prisons asks the question, Why are so many black men in prison?

Christina Kubisch: Sky Lights

Using simple acts of light and sound, viewers’ perceptions were heightened to the sounds of silence and visions of nothing

Winifred Lutz: Serving Time

Three side-by-side cells embody a mirror of time’s passage, encouraging plants to grow and flour to mildew

Virgil Marti: for Oscar Wilde

Celebrating the 100th anniversary of Oscar Wilde’s incarceration for “gross indecency with other men” Marti pays homage by restoring a cell, wallpapering it with silkscreened Wilde witticisms, with hundreds of lilies covering the floor leading to the cell, reiterating the peeling institutional green and white paint.

Bruce Pollock: Vas Hermeticus

Using the penitentiary’s radial design as a metaphorical mandala, a symbol of wholeness, Pollock’s piece comments on the spiritual forces present but hidden in prison design. Vas Hermeticus translates to “sealed container” of alchemical transformation, a corollary of the criminal rehabilitation philosophy.

Fiona Templeton with Amnesty International: Cells of Release

Templeton provided visitors with the possibility of active participation in the world through engagement with the installation. With the assistance of Amnesty International, the cells were installed with up-to-date information on prisoners of conscience incarcerated throughout the world, and visitors were encouraged to use the writing supplies to write letters of appeal on behalf of these prisoners.

Allan Wexler : Cell

Wexler’s installation was a meditation on the infinite potential of common things. The cell was carefully and austerely redesigned to provide for the basic comforts of a fictive artist-inmate. Materials available within the limits of a prison such as toilet paper, catsup and coffee, stretched towards the limits of their physical properties become raw materials for new inventions.

Catalogue available.